Search

Guideline 13.7 – Medication or Fluids for the Resuscitation of the Newborn

Summary

Guidelines 13.1-13.10 and the Newborn Life Support algorithm are provided to assist in the resuscitation of newborn infants. Differences from the adult and paediatric guidelines reflect differences in the anatomy and physiology and the causes of cardiorespiratory arrest for newborns, older infants, children and adults. These guidelines draw from Neonatal Life Support 2020 and 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR) 1, 2 the development of which included representation from ANZCOR. The 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Care 3 and local practices have also been taken into account.

To whom do these guidelines apply?

The term ‘newborn’ or ‘newborn infant’ refers to the infant in the first minutes to hours following birth. In contrast, the neonatal period is defined as the first 28 days of life. Infancy includes the neonatal period and extends through the first 12 months of life.

ANZCOR Guidelines 13.1 to 13.10 and the Newborn Life Support algorithm are mainly for the care of newborns. The exact age at which paediatric techniques and in particular, compression-ventilation ratios, should replace the techniques recommended for newborns is unknown, especially in the case of very small preterm infants. For term infants beyond the first minutes to hours following birth, and particularly in those with known or suspected cardiac aetiology of their arrest, paediatric techniques may be used (refer to Paediatric Advanced Life Support Guidelines 12.1 to 12.7).

Who is the audience for these guidelines?

ANZCOR Guidelines 13.1 to 13.10 and the Newborn Life Support algorithm are for health professionals and those who provide healthcare in environments where equipment and drugs are available (such as a hospital). When parents are taught CPR for their infants who are being discharged from birth hospitals, the information in Basic Life Support Guidelines (ANZCOR Guidelines 2 to 8) is appropriate.

Recommendations

The Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation (ANZCOR) makes the following recommendations:

- Ventilation and chest compressions must be delivered continuously during preparation to administer IV medication or fluids. [Good Practice Statement]

- An umbilical vein catheter (UVC) is the suggested intravascular route for adrenaline (epinephrine) and it can also be used for fluid administration. [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence] It can also be used for continued vascular access until an alternative route is established after admission to a neonatal unit. [Good Practice Statement]

- ANZCOR suggests that if the heart rate has not increased to 60 beats per minute or greater after optimising ventilation and chest compressions, then intravascular adrenaline (epinephrine) should be given as soon as possible. [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence]

- ANZCOR suggest that the recommended intravenous dose is 10 to 30 microgram/kg (0.1 to 0.3 mL/kg of a 1:10,000 solution) by a quick push [Weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence] (1 mL contains 0.1mg of adrenaline (epinephrine), so 0.1 mL = 10 microgram of adrenaline (epinephrine)). It should be followed by a small 0.9% sodium chloride flush. ANZCOR suggests that this dose can be repeated every 3 to 5 minutes if the heart rate remains <60 beats per minute despite effective ventilation and cardiac compressions. 1, 4 [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

- If vascular access is not yet available, ANZCOR suggests administering endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine). [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence] If the endotracheal dose fails to increase heart rate to > 60 beats per min then an intravascular dose should be given as soon as feasible, and administration of endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine) should not delay attempts to establish vascular access. [Good Practice Statement]

- ANZCOR suggests that intraosseous lines can be used as an alternative, especially if umbilical or direct venous access is not available. The choice of route may depend on local availability of equipment, training and experience. [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

- There is insufficient evidence for the use of endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine), but it is likely that a higher dose will be required to achieve similar blood levels and effect. ANZCOR suggests that if the tracheal route is used, doses of 50-100 microgram /kg (0.5-1 mL/kg of a 1:10,000 solution) should be given. [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

- Intravascular fluids should be considered when there is suspected blood loss, the newborn appears to be in shock (pale, poor perfusion, weak pulse) and has not responded adequately to other resuscitative measures. 1 [Good Practice Statement] Isotonic crystalloid (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride or Hartmann’s solution) should be used in the first instance, but may need to be followed with red cells and other blood products suitable for emergency transfusion, in the setting of critical blood loss. Use of a specific protocol is suggested whenever critical blood loss is suspected. [Good Practice Statements]

- Since blood loss may be occult, in the absence of history of blood loss, a trial of volume administration may be considered in newborns who are not responding to resuscitation. [Good Practice Statement]

- The initial dose of intravascular volume expanding fluid is 10 mL/kg given by IV push (over several minutes). This dose may be repeated after observation of the response. [Good Practice Statements]

Abbreviations

|

Abbreviation |

Meaning/Phrase |

|

ANZCOR |

Australian and New Zealand Committee on Resuscitation |

|

CI |

Confidence interval (95%) |

|

CoSTR |

International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations |

|

CPR |

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

|

IO |

Intraosseous |

|

IV |

Intravenous |

|

UVC |

Umbilical venous catheter |

Guideline

Medications and fluids are rarely indicated for resuscitation of newborn infants. 1, 2, 5

Bradycardia is usually caused by hypoxia and inadequate ventilation. Apnoea is due to insufficient oxygenation of the brainstem. Therefore, establishing adequate ventilation is the most important step to improve the heart rate. However, if the heart rate remains less than 60 beats per min despite adequate ventilation (chest is seen to move with inflations) and chest compressions, adrenaline (epinephrine) may be needed. As adrenaline (epinephrine) exerts part of its effect by action on the heart it is important to give it as close to the heart as possible, ideally as a rapid bolus through an umbilical venous catheter.

Ventilation and chest compressions must be delivered continuously during preparation to administer IV medication or fluids. [Good Practice Statement]

Routes of Administration

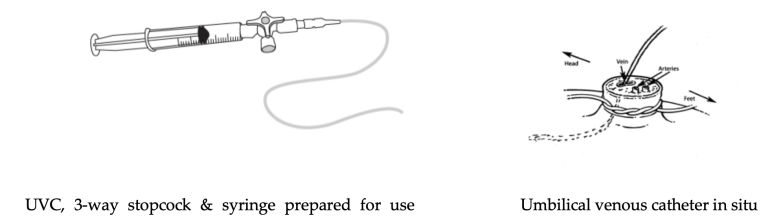

Umbilical vein

An umbilical vein catheter (UVC) is the suggested intravascular route for adrenaline (epinephrine) and it can also be used for fluid administration. It can also be used for continued vascular access until an alternative route is established after admission to a neonatal unit. [Good Practice Statement] Blood gases obtained from the UVC during resuscitation are sometimes useful in guiding treatment decisions.

Endotracheal tube

Vascular access for adrenaline (epinephrine) is a high priority in any newborn receiving chest compressions. There is little research to support the use of endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine) and there are concerns that even in higher doses, it may still result in lower levels of adrenaline (epinephrine) and have lower efficacy than the intravenous route.6 If vascular access is not yet available, ANZCOR suggests administering endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine). 1 [CoSTR 2020 Weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence.] If the endotracheal dose fails to increase heart rate to > 60 beats per min then an intravascular dose should be given as soon as feasible, and administration of endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine) should not delay attempts to establish vascular access. [Good Practice Statement]

Peripheral vein

Inserting a peripheral venous cannula can be very difficult in a shocked newborn and can take too long.

Intraosseous lines

Intraosseous (IO) lines are not commonly used in newborns because of the more readily accessible umbilical vein, the fragility of small bones and the small intraosseous space, particularly in a preterm infant. However, ANZCOR suggests this route can be used as an alternative, especially if umbilical or direct venous access is not available. 1, 7 [CoSTR 2020, Weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

Outside of a hospital birthing suite setting, we suggest that either venous or IO routes may be used to administer fluids and medications during newborn resuscitation. ANZCOR suggests the choice of route may depend on local availability of equipment, training and experience. 1, 7 [CoSTR 2020, Weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

There are a number of case reports of serious adverse effects of IO access in newborns, including tibial fractures and extravasation of fluids or medications resulting in compartment syndrome and amputation. In contrast, the rate of adverse effects attributable to emergency umbilical venous access is unknown. 1, 7

Umbilical artery

The umbilical artery is not recommended for administration of resuscitation drugs. There are serious concerns that complications may result if hypertonic or vasoactive drugs (e.g., adrenaline (epinephrine)) are given into an artery.

Types and Doses of Medications

Adrenaline (epinephrine)

Indications

ANZCOR suggest that if the heart rate has not increased to 60 beats per minute or greater after optimising ventilation and chest compressions, then intravascular adrenaline (epinephrine) should be given as soon as possible. 1 [CoSTR 2020, weak recommendation, very low certainty evidence]

Animal research indicates that chest compressions without adrenaline (epinephrine) are insufficient to increase cerebral blood flow.8 There is the potential for long delays (up to several minutes) in establishing intravascular access and administering adrenaline (epinephrine). Nevertheless, an animal study suggests plasma concentrations are higher and are achieved sooner after administration, and there are higher rates of return of spontaneous circulation when the intravascular route is used, (despite lower intravascular than endotracheal doses). 6 We have put lower value on the absence of human newborn studies that clearly demonstrate benefit of adrenaline (epinephrine) administration, or that demonstrate advantage of intravascular vs. endotracheal epinephrine. 4

Dosage

The suggested intravenous dose is 10 to 30 microgram/kg (0.1 to 0.3 mL/kg of a 1:10,000 solution) by a quick push [weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence] (1 mL contains 0.1mg of adrenaline (epinephrine), so 0.1 mL = 10 microgram of adrenaline (epinephrine)). It should be followed by a small 0.9% sodium chloride flush. ANZCOR suggests that this dose can be repeated every 3 to 5 minutes if the heart rate remains <60 beats per minute despite effective ventilation and cardiac compressions. 1, 4 [CoSTR 2020, Weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

The studies in newborns are inadequate to recommend routine use of higher doses of adrenaline (epinephrine). Based on studies in children and young animals, higher doses may increase risk of post-resuscitation mortality and risk of intracranial haemorrhage and are not recommended. 4, 9-11

There is insufficient evidence for the use of endotracheal adrenaline (epinephrine), but it is likely that a higher dose will be required to achieve similar blood levels and effect. ANZCOR suggests that if the tracheal route is used, doses of 50-100 microgram/kg (0.5-1 mL/kg of a 1:10,000 solution) should be given. 1, 4, 12, 13 [CoSTR 2020, Weak recommendation, very low certainty of evidence]

Volume Expanding Fluids

Indications

Intravascular fluids should be considered when there is suspected blood loss, the newborn appears to be in shock (pale, poor perfusion, weak pulse) and has not responded adequately to other resuscitative measures. 1 [Good Practice Statement] Isotonic crystalloid (e.g. 0.9% sodium chloride or Hartmann’s solution) should be used in the first instance, but may need to be followed with red cells and other blood products suitable for emergency transfusion, in the setting of critical blood loss. Use of a specific protocol is suggested whenever critical blood loss is suspected. 14 [Good Practice Statements]

Since blood loss may be occult, in the absence of history of blood loss, a trial of volume administration may be considered in newborns who are not responding to resuscitation. 1 [Good Practice Statement] However, in the absence of history of blood loss, there is limited evidence of benefit from administration of volume during resuscitation unresponsive to chest compressions and adrenaline (epinephrine) 15 [LOE IV], and some suggestion of harm from animal studies 16, 17 [Extrapolated evidence]

Dosage

The initial dose is 10 mL/kg given by IV push (over several minutes). This dose may be repeated after observation of the response. 1 [Good Practice Statements]

References

- Wyckoff MH, Wyllie J, Aziz K, de Almeida MF, Fabres JW, Fawke J, et al. Neonatal Life Support 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2020;156:A156-A87.

- Wyllie J, Perlman JM, Kattwinkel J, Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Guinsburg R, et al. Part 7: Neonatal resuscitation: 2015 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Resuscitation. 2015;95:e169-201.

- Aziz K, Lee HC, Escobedo MB, Hoover AV, Kamath-Rayne BD, Kapadia VS, et al. Part 5: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16_suppl_2):S524-s50.

- Isayama T, Mildenhall L, Schmolzer GM, Kim HS, Rabi Y, Ziegler C, et al. The Route, Dose, and Interval of Epinephrine for Neonatal Resuscitation: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4).

- Kapadia P, Hurst C, Harley D, Flenady V, Johnston T, Bretz P, et al. Trends in neonatal resuscitation patterns in Queensland, Australia - A 10-year retrospective cohort study. Resuscitation. 2020;157:126-32.

- Vali P, Chandrasekharan P, Rawat M, Gugino S, Koenigsknecht C, Helman J, et al. Evaluation of timing and route of epinephrine in a neonatal model of asphyxial arrest. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(2):e004402.

- Granfeldt A, Avis SR, Lind PC, Holmberg MJ, Kleinman M, Maconochie I, et al. Intravenous vs. intraosseous administration of drugs during cardiac arrest: A systematic review. Resuscitation. 2020;149:150-7.

- Sobotka KS, Polglase GR, Schmolzer GM, Davis PG, Klingenberg C, Hooper SB. Effects of chest compressions on cardiovascular and cerebral hemodynamics in asphyxiated near-term lambs. Pediatr Res. 2015;78(4):395-400.

- Perondi MB, Reis AG, Paiva EF, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA. A comparison of high-dose and standard-dose epinephrine in children with cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(17):1722-30.

- Berg RA, Otto CW, Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Sanders AB, Henry CP, et al. A randomized, blinded trial of high-dose epinephrine versus standard-dose epinephrine in a swine model of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(10):1695-700.

- Burchfield DJ, Preziosi MP, Lucas VW, Fan J. Effects of graded doses of epinephrine during asphxia-induced bradycardia in newborn lambs. Resuscitation. 1993;25(3):235-44.

- Crespo SG, Schoffstall JM, Fuhs LR, Spivey WH. Comparison of two doses of endotracheal epinephrine in a cardiac arrest model. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(3):230-4.

- Jasani MS, Nadkarni VM, Finkelstein MS, Mandell GA, Salzman SK, Norman ME. Effects of different techniques of endotracheal epinephrine administration in pediatric porcine hypoxic-hypercarbic cardiopulmonary arrest. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(7):1174-80.

- Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 6 - Neonatal and Paediatrics Canberra, Australia2016. Available from: https://www.blood.gov.au/patient-blood-management-guidelines-module-6-neonatal-and-paediatrics.

- Wyckoff MH, Perlman JM, Laptook AR. Use of volume expansion during delivery room resuscitation in near-term and term infants. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):950-5.

- Wyckoff M, Garcia D, Margraf L, Perlman J, Laptook A. Randomized trial of volume infusion during resuscitation of asphyxiated neonatal piglets. Pediatr Res. 2007;61(4):415-20.

- Mayock DE, Gleason CA. Cerebrovascular effects of rapid volume expansion in preterm fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2004;55(3):395-9.

About this Guideline

|

Search date/s |

ILCOR literature search details and dates are available on the CoSTR page of the ILCOR website (https://costr.ilcor.org) and the relevant CoSTR documents. 1, 2 |

|

Questions/PICOs: |

Are described in the CoSTR documents (https://costr.ilcor.org) |

|

Method: |

Mixed methods including ARC NHMRC methodology before 2017 and ILCOR GRADE methodology described in ILCOR publications since 2017. |

|

Principal reviewers: |

Helen Liley, Lindsay Mildenhall, Marta Thio and Callum Gately |

|

Main changes |

Updated statements about use of intraosseous lines and use of adrenaline (epinephrine). Updating of review evidence, references, and terminology to increase consistency with GRADE terminology. |

|

Approved: |

April 2021 |

Referencing this guideline

When citing the ANZCOR Guidelines we recommend:

ANZCOR, 2026, Guideline 13.7 – Medication or Fluids for the Resuscitation of the Newborn , accessed 5 March 2026, https://www.anzcor.org/home/neonatal-resuscitation/guideline-13-7-medication-or-fluids-for-the-resuscitation-of-the-newborn